|

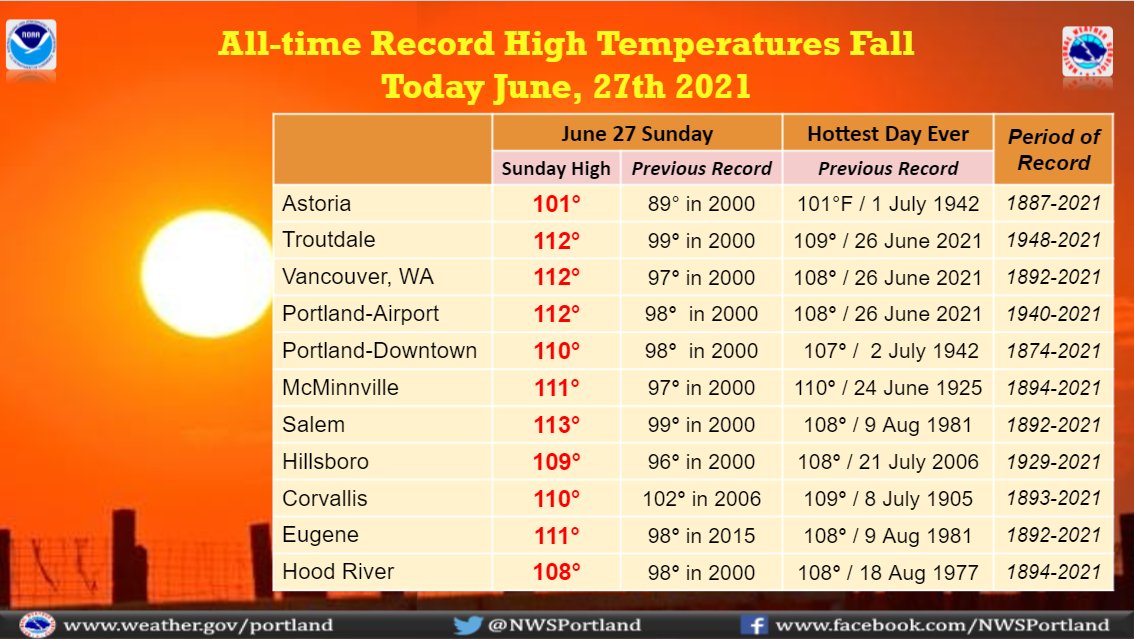

Across the US and Canadian Pacific Northwest, a once in a millennium, climate change-fueled heatwave engulfed in the region. Average high temperatures in the area are a mild 74°F (Portland), 71°F (Seattle), and 67°F (Vancouver, BC). Historical records for high temperatures were demolished: the temperature at PDX (Portland’s international airport) set all-time records on back-to-back days (June 26: 109°F; June 27: 112°F), in addition to setting a day-of record (the previous record for June 27 was 98°, set in 2000). 1-in-5 homes in Portland are without air conditioning. Just a few hours north in Seattle, that number increases to 56%, where yesterday’s high temperature was 104°F (a day-of, monthly, and all-time record). So, the question is what can folks do now to cope with climate change? We know the big-picture solution is a systemic change that repairs our relationship with the planet and each other, but when climate change happens in any given corner of the globe, what do people do? When climate change revs up the intensity of flooding, tropical storms, or blizzards, we plainly see the damage, disruption, and despair. But with heat, we don’t see it quite so clearly. Yesterday, I – along with my girlfriend, our dog, and tens-of-thousands (if not more) of people in the region – were climate migrants for the day. As often is the case in the Willamette Valley of Oregon, when the temperatures get into the 90s, the Oregon Coast is our refuge. The cool waters of the northeast Pacific help keep the Oregon Coast several degrees cooler than areas of the Willamette Valley (June mean-high temp for Newport, OR: 61°F). Like clockwork, as the forecasts for extreme heat were announced, a mass exodus to the coast occurred. I found myself escaping to the town of Yachats (Yah-HAWTS), where temperatures were relatively cool 78°F. I don’t know how many of my fellow migrants experienced this same sense of existential dread, but I felt like a prisoner of climate change as I put the key in the ignition of my internal-combustion engine car, turned it on, and spewed 0.081 tons of CO2 to escape a problem caused by spewing too much CO2. What the actual-fuck?! I didn’t have to do more than eavesdrop on some conversations at the beach to get my answer. Two quotes in particular got my ears to perk-up. The first: Anything above 90°F is all the same As someone who just recently completed a PhD in geography, studying the impacts of climate change on the ocean, this intrigued me. The psychology of climate change is amazing. There is a very real difference between 90°F and the 111°F this person was escaping from Eugene, OR, but any chance of that difference mattering to the person was squashed by a reply from the person they were talking with (referring to the conditions at the beach in Yachats at that moment): It’s like Key West (Florida) in November This was the sign I was looking for. In the face of climate change, we are all looking for a sense of normal. Familiarity. Escape. Instead of talking about the problem (climate change), solutions (pushing for systemic change and improving personal decisions), or the utter irony of thousands of people firing up their CO2 producing cars to escape the problem, they just imagined themselves in Key West. This is just speculation, but I don’t think my friends on the beach are aware of how climate change is causing just as much havoc in the Florida Keys. I ended my “day as a climate migrant” by driving back into the Willamette Valley, to Corvallis, where the temperature was 102°F at 7pm. Temperatures didn’t drop below 100°F until after midnight. As I write this, I can’t help but think about all of the other climate change catastrophes I’ve experienced over the past 8 years: mass coral bleaching, rapidly intensifying typhoons, and wildfires. I can now add the “heat dome” I’m sitting in to the long list of climate impacts that are becoming much more normal than an idyllic day in the Florida Keys. The worst-case scenario, I imagine, is when we long for a single day as a climate migrant – as opposed to being permanent climate migrants. If we don’t treat climate change like the emergency it is, I fear that that very scenario will become our new normal.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

Steven M. Johnson

Aloha and Hafa Adai! I'm an Assistant Professor at Cornell University. As a researcher and knowledge enthusiast, I enjoy learning about social-ecological systems, the ocean, and the people who rely on it. Archives

April 2022

Categories |

Location

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed