|

About two months ago, I was contacted by an editor from Science asking if I'd be interested in writing a book review. While this isn't the exact interaction I envisioned me having with an editor at Science, I had to say, "yes!"

I'm an avid reader of books, so getting to read a pop-science book AND review it is somewhat of a dream come true for me. It was a different type of writing than most of the stuff I do and it was a fun challenge. Here's the link, so please check it out and let me know what you think (also, check out the book itself!). https://www.science.org/stoken/author-tokens/ST-415/full

0 Comments

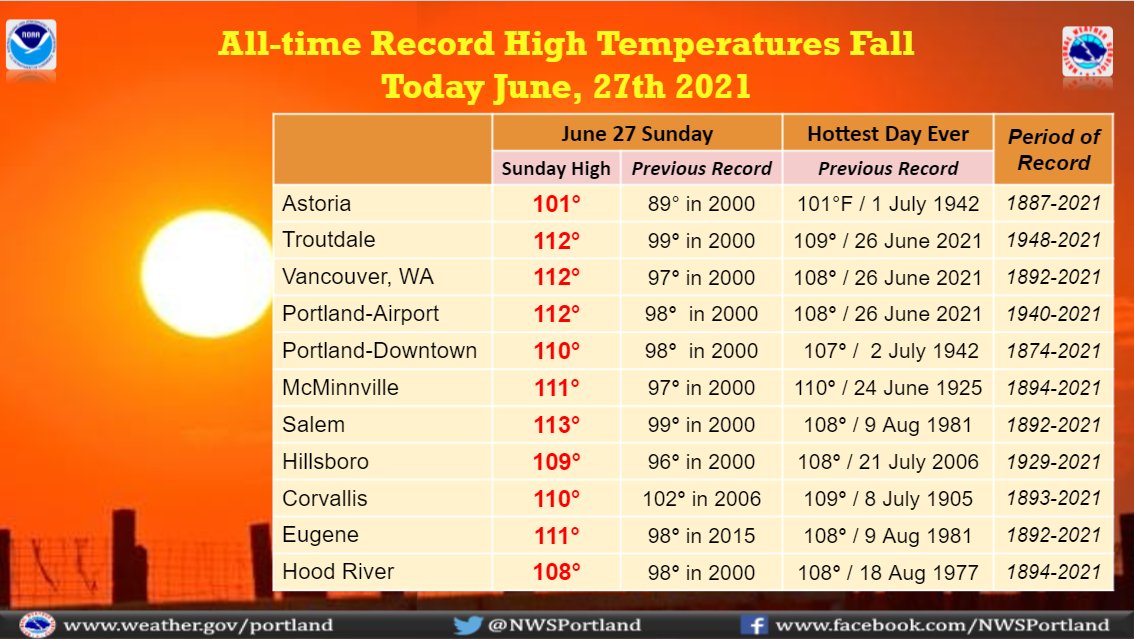

Across the US and Canadian Pacific Northwest, a once in a millennium, climate change-fueled heatwave engulfed in the region. Average high temperatures in the area are a mild 74°F (Portland), 71°F (Seattle), and 67°F (Vancouver, BC). Historical records for high temperatures were demolished: the temperature at PDX (Portland’s international airport) set all-time records on back-to-back days (June 26: 109°F; June 27: 112°F), in addition to setting a day-of record (the previous record for June 27 was 98°, set in 2000). 1-in-5 homes in Portland are without air conditioning. Just a few hours north in Seattle, that number increases to 56%, where yesterday’s high temperature was 104°F (a day-of, monthly, and all-time record). So, the question is what can folks do now to cope with climate change? We know the big-picture solution is a systemic change that repairs our relationship with the planet and each other, but when climate change happens in any given corner of the globe, what do people do? When climate change revs up the intensity of flooding, tropical storms, or blizzards, we plainly see the damage, disruption, and despair. But with heat, we don’t see it quite so clearly. Yesterday, I – along with my girlfriend, our dog, and tens-of-thousands (if not more) of people in the region – were climate migrants for the day. As often is the case in the Willamette Valley of Oregon, when the temperatures get into the 90s, the Oregon Coast is our refuge. The cool waters of the northeast Pacific help keep the Oregon Coast several degrees cooler than areas of the Willamette Valley (June mean-high temp for Newport, OR: 61°F). Like clockwork, as the forecasts for extreme heat were announced, a mass exodus to the coast occurred. I found myself escaping to the town of Yachats (Yah-HAWTS), where temperatures were relatively cool 78°F. I don’t know how many of my fellow migrants experienced this same sense of existential dread, but I felt like a prisoner of climate change as I put the key in the ignition of my internal-combustion engine car, turned it on, and spewed 0.081 tons of CO2 to escape a problem caused by spewing too much CO2. What the actual-fuck?! I didn’t have to do more than eavesdrop on some conversations at the beach to get my answer. Two quotes in particular got my ears to perk-up. The first: Anything above 90°F is all the same As someone who just recently completed a PhD in geography, studying the impacts of climate change on the ocean, this intrigued me. The psychology of climate change is amazing. There is a very real difference between 90°F and the 111°F this person was escaping from Eugene, OR, but any chance of that difference mattering to the person was squashed by a reply from the person they were talking with (referring to the conditions at the beach in Yachats at that moment): It’s like Key West (Florida) in November This was the sign I was looking for. In the face of climate change, we are all looking for a sense of normal. Familiarity. Escape. Instead of talking about the problem (climate change), solutions (pushing for systemic change and improving personal decisions), or the utter irony of thousands of people firing up their CO2 producing cars to escape the problem, they just imagined themselves in Key West. This is just speculation, but I don’t think my friends on the beach are aware of how climate change is causing just as much havoc in the Florida Keys. I ended my “day as a climate migrant” by driving back into the Willamette Valley, to Corvallis, where the temperature was 102°F at 7pm. Temperatures didn’t drop below 100°F until after midnight. As I write this, I can’t help but think about all of the other climate change catastrophes I’ve experienced over the past 8 years: mass coral bleaching, rapidly intensifying typhoons, and wildfires. I can now add the “heat dome” I’m sitting in to the long list of climate impacts that are becoming much more normal than an idyllic day in the Florida Keys. The worst-case scenario, I imagine, is when we long for a single day as a climate migrant – as opposed to being permanent climate migrants. If we don’t treat climate change like the emergency it is, I fear that that very scenario will become our new normal.

America's climate catastrophe is here and we have nowhere to hide. Our options? Act as though our lives depend on it because they do. For many American’s this week, the infernos blazing up and down the west coast are a stark reminder that climate change is the existential threat of our lifetime. Eerily post-apocalyptic skies over San Francisco and ashen ghost towns across Oregon, American’s are left wondering: is there anywhere to seek shelter from the coming storm? The sad answer to this question is simple: there is no escaping the climate catastrophe. While this week’s events are some people’s first experience with climate change, others have been dealing with these impacts for years and I am one of them. Typhoons Millions of Americans live in the US overseas territories: Puerto Rico, the US Virgin Islands, American Samoa, Guam, and the Northern Mariana Islands. Like most islands around the world, these places contribute the least to global CO2 emissions but are often the first to experience the dire consequences. I grew up on the island of Saipan, the main island in the Northern Mariana Islands. Climate change has been unfolding there in several ways over the past decade. In 2013, the island – along with its neighbor to the south, Guam – experienced widespread coral bleaching that decimated up to 90% of the nearshore reefs, which are traditional fishing grounds for the indigenous CHamoru and Refalawasch people. Under the best conditions, where reefs aren’t subjected to continued disturbances, recovery can take place in five to ten years. Unfortunately, the conditions that led to this decline persisted for four straight years. While islands are rightfully thought for their marine habitats, impacts of climate change are also felt on land. After back-to-back summers of lethal water temperatures, on 2 August 2015 Typhoon Soudelor decimated Saipan in ways unexpected by even the most experienced of meteorologists. At the time, National Weather Service meteorologist Chip Guard described the storm as “unique”. Guard also went on to say, “It’s a storm we really have not seen go over populated areas” and “the rate that it was intensifying was much faster than we expected it to intensify.” These are the exact predictions that scientists have been warning the public about for decades. Another prediction made by climate scientists is that the intensity of storms – storms like Soudelor – would become more frequent. Three short years later, Saipan was confronted with the painful reality of these predictions. Super Typhoon Yutu made landfall on 25 October 2018. Barely recovered from the devastation of Soudelor, Yutu pummeled the island like few storms before it. Some of the island residents were still living in makeshift shelters when the storm arrived. The headlines surrounding the storm were startling:

Aftermath of Typhoon Soudelor (Photograph: Raymond Zapanta/Saipan Tribune) Tinderboxes Currently, I live in Corvallis, Oregon, where I’m working on my PhD in geography and study climate change impacts on the ocean and the people who depend on them (spoiler: we all depend on the health of the ocean). When I moved to the Pacific Northwest, I knew it had a reputation for being rainy and generally mild concerning extreme weather. It doesn’t get hurricanes; too warm to get blizzards; too mountainous for tornados (although one does have to worry about this). These safeguards are beginning to fail as we lurch further into the Anthropocene – the geological era where humans are the main driver of global environmental change. The ongoing coverage and analysis of the recent fires point to two contributing factors: climate change and fire management in our forests. Predictably, these drivers are being politicized – as they usually are when climate change is a part of the equation - at a time when they need to be humanized. Regardless of which side of the aisle you find yourself on, the root cause of the problem is clear: humans have abused the natural environment and are now dealing with a tinderbox and it is our responsibility to deal with it. Pain, suffering, and loss due to climate change are, unfortunately, unavoidable at this point. We have collectively dragged our feet on this issue for far too long. But not all hope is lost. We can still take action to make our communities as resilient as possible to the climate catastrophe. Whether we find ourselves in Saipan or Oregon, some solutions can help us weather the coming storm, reconnect with the natural world, and – perhaps most importantly – restore dignity and respect with each other. A search and rescue team looks for victims in the aftermath of the Almeda fire in Talent, Oregon Sunday. (Photograph: Adrees Latif/Reuters) Tools & Tactics So, how do we make it through with heads and hearts intact? There are many choices but let’s highlight two simple solutions that we can put into place in now to give us the best fighting chance. Learn from the pastMany of the environments that are currently being assaulted by the climate breakdown are traditional homes to indigenous people, tribes, and First Nations. For centuries these people observed, experimented, and codified the socio-environmental into a body knowledge some call traditional ecological knowledge. You might know it by another name: culture. And the process that these people undertook to develop their culture? Science! By recognizing, elevating, and integrating the cultural practices of indigenous people, we can support ecosystem resilience, whether that be on a coral reef or a fire-dependent landscape. Plan for the future I’m not going to tip-toe around this one: the most powerful and consequential tool we have at our disposal when it comes to planning for the future is our vote. Surviving climate catastrophe requires leadership, coordination, and a plan. The absence of a plan is nothing short of planetary suicide. The denial of the problem is nihilism. On 3 November 2020, we are tasked with whether we want a plan – a fighting chance – that brings people together to overcome this existential threat or if we’d rather wait and hope for a miracle.

We have nowhere left to run from this problem. I’ve been on far-flung tropical islands and dealt with climate change. I’ve been nestled in the foothills of majestic Doug Fir forests and climate change has found me. Running is no longer an option and if we concede to hiding, we lose. The actions we take today, tomorrow, in November, and every day after that are our only options left. Act as though our lives depend on it because they do. This space is usually reserved for my professional work but seeing as we're in the midst of some of the craziest times, I've decided to use this space more openly to discuss what's on my mind. More likely than not, it will be work-related, but occasionally it will be something more personal. I hope you enjoy the detours.

Over at least the next 2.5 months there will be lots of discussion surrounding Sen. Kamala Harris and her ethnicity. Something likely to be missing from the conversation is the topic of privilege. Not the privilege that Kamala Harris finds herself in as a sitting US Senator, with what is looking like a very good shot at being the next Vice President, but the privilege of those commenting on her ethnicity. A vast majority of the chatter surrounding her ethnicity will come from either privileged white cis-males or privileged people of color. I will probably get a lot of blowback for attaching privilege to the latter but in the context of this discussion, they do have privilege. People in these groups – and all monoethnic groups for that matter – have the privilege of not having to defend this part of their identity. Monoethnic individuals will undoubtedly face trials and tribulations, but they have a privilege that multiethnic people do not: they get to be gatekeepers of their ethnicity and thus have the ability to otherize and ostracize those who don’t meet a standard. Gatekeepers of identity often look to set standards for inclusion that center around shared histories, experiences, or cultural values. Many critics of Kamala Harris’s claims of being African American will look to her Jamaican heritage and say, “she’s not the descendent of American slaves.” True. But this answer begs an even more important question: what are the differences between American and Jamaican (British) slavery? Slavery under the British Empire was abolished in 1833, which included the overseas territories like Jamaica. America would abolish slavery in 1865. Twenty-two years is the difference. Black American’s would suffer under a failed Reconstruction and Jim Crow laws for an additional 100 years until 1965. Meanwhile, Jamaica would remain a British Colony, subject to rule by the British Parliament and Crown, until it gained its independence in 1962. Needless to say, race relations between Blacks and whites in both countries were and remain fraught. So, what are the differences between American and Jamaican slavery? It would be much simpler and easier to answer how American and Jamaican slavery are similar. The Atlantic slave trade was a vile economic system that exploited and dehumanized people from all parts of Africa. Destinations for slaves included both Jamaica and America. Framing this in the crude terms of economics, the supply chains are the same but the end customers were different. Kamala Harris’s ancestors did not choose to get on the ship bound for Jamaica – chance made that decision for them. Instead of debating the particulars and continuing to propose strict standards, people with the privilege of a defined ethnic identity should seek to understand the unique burden of being multiethnic. They are often the product of individuals who embraced the differences between us, not the outcome of failed gatekeeping and poor taxonomy. Multiethnic individuals don’t choose to be half this and half that. They don’t seek to be “approachably brown” or a “light-skinned brother.” Just ask President Barack Obama, comedian Trevor Noah, reggae superstar Bob Marley, and Kamala Harris about their experiences defending the everyday realities of being multiethnic. As the recent mass editing of Kamala Harris’s Wikipedia page shows, everyone has a strong opinion on this matter. Moderators for the website have resolved the issue but the fact that so many people found it to be of the utmost importance to determine the proper label for a person with parents from Jamaica and India is concerning. Yes, the histories of these places and the people from them are complicated, but accepting that people can be Black and Asian at the same time shouldn’t.

Covid-19.

Social distancing. 2020 is proving to be a banner year in global social-ecological change. The spread of coronavirus has been a wake up call for the parts of society who've felt immune to the worlds problems. Sooner or later, no amount of social capital will keep us immune from short sighted greed. However, it doesn't have to be all doom and gloom. To help navigate these times, it's a good practice to balance out the barrage of headlines with some escapism. For me, that's running and music. I've put together a playful social distancing playlist to help take the edge off. Enjoy and be healthy. Hau`oli makahiki hou (Happy New Year)!

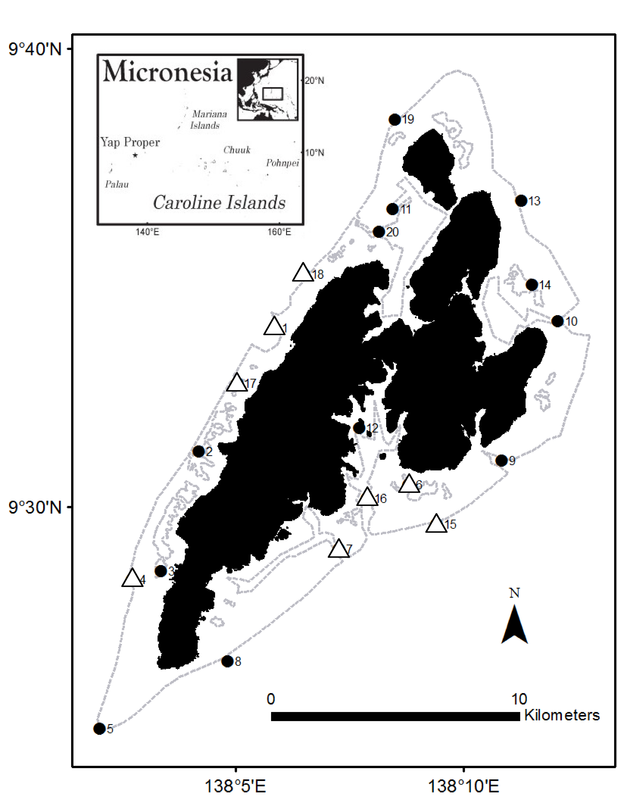

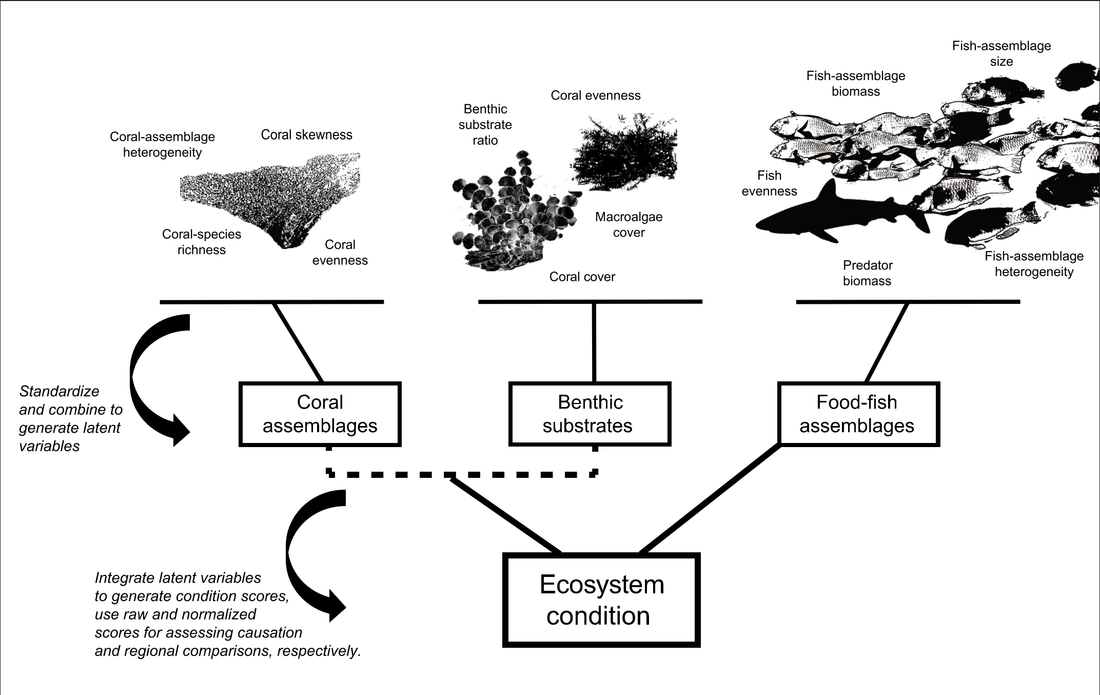

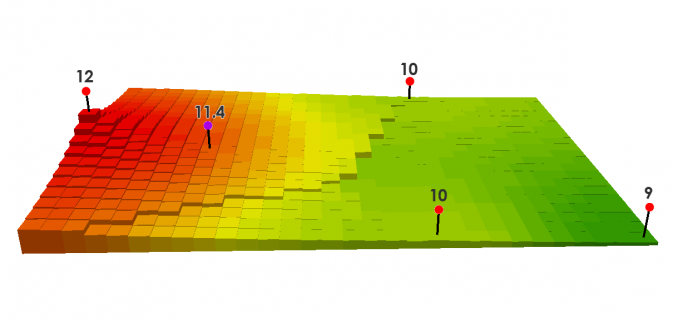

2018 has come to a close and it was a year that brought along many opportunities, successes, and challenges that lay the foundation for 2019, which I hope to be just as promising a year as 2018. Here is a short recap of my year: SESYNC Graduate Pursuits: Coral Stories The National Socio-Environmental Synthesis Center (SESYNC) in Annapolis, MD is a NSF funded think-tank dedicated to addressing the world's pressing socio-environmental problems by supporting interdisciplinary research teams that design and implement research programs. One of the funding opportunities provided by SESYNC is a called the graduate pursuit. This program targets PhD students to self-select and self-design a research proposal for funding by SESYNC. I was fortunate enough to successfully co-lead a team of amazing and diverse students from around the world (we have international students and US students studying abroad) through the review process. Our project is trying to better understand if the way we talk about environmental systems in the media impacts the way we manage these systems. Our team is using coral reefs as our focal system and will be carrying out an analysis in three focal regions. Here is a description of our study. Also, be sure to follow our Twitter @CoralStories for updates on the project, as well as to keep up with all of the news and research our team finds interesting! Super Typhoon Yutu In October, Super Typhoon Yutu ravaged my home island of Saipan and the neighboring island, Tinian. Saipan and Tinian are hit by typhoons practically every year, but this was no ordinary storm. In a year that had both Hurricane Florence and Michael, this storm dwarfed both in terms of strength, but was a barely a blip on the radar when it comes to media coverage. It wasn't until days and weeks later that coverage from major US media outlets began to cover the storm and the plight of the people living there. Ironically, some of the stories were about how the media was NOT covering the storm. Despite all of that, the people of Saipan and Tinian displayed true grit and showed the resilience of island communities when faced with turmoil. Several of the diaspora from back home took to social media to do what we could for our home and its people. This activity led to a blog post I worked on with Alyssa Frederick (@paua_biologist) for the Union of Concerned Scientists, where we talk about the responsibility the scientific community has when it comes to using our power and privilege to speak up for the people who live in the places we study. 2019: bring on more challenges As I begin the new year, I hope for more challenges professionally and personally. I hope to struggle and have fun at the same time. This photo of me as I'm about to cross the finish at my first 50 km race in 2018 sums up how I hope next year works out - a lot of big climbs, but still able to cross the finish line! I'm currently enrolled in a GIS course for my PhD program. We had the option of a final or a course project - I opted for the latter option. I decided to combine work from here and here. We needed to create a poster or website, so I'm posting my work here. Show me the money: using spatial interpolation of coral reef ecosystem indicators to support management decision making. Steven M. Johnson, Geography - CEOAS, Oregon State University. GEOG 561 - GIScience II: Analysis & Applications Introduction Coral reefs are some of the most diverse and dynamic ecosystems on the planet. Home to over 1 million species, they cover less than 1% of the worlds surface. However, coral reefs around the world are threatened by pollution [1], overfishing [2], and global climate change [3]. A challenge for coastal communities who rely on these ecosystems for their livelihoods is finding ways to maintain ecosystem resilience [4]. While the ultimate goal is to keep the planet within the habitable boundaries of reefs [5], managing for resilience seems to be our best bet[6]. Managing for resilience can take many shapes, including fisheries regulations [7] or marine protected areas [8]. However, a challenge remains in measuring resilience and identifying where these reefs are located. Coral reef resilience is typically assessed using underwater visual surveys. The inherent complexity of coral reefs makes quantifying resilience challenging [9], requiring the use of other analytical techniques. Spatial statistical techniques have been gaining increased utility in coral reef management and conservation [10–12]. Spatial interpolation techniques can help identify potential areas for management and conservation support. Using underwater census data on ecosystem health, I used two interpolation techniques (inverse distance weighted (IDW) and kriging) to “fill-in” data between monitoring stations on Yap, Micronesia (Fig. 1). Methods Ecosystem condition Ecosystem condition indicators were defined based on13 (Fig. 2). These indicators capture many of the key functional components of ecosystem health. Condition score is assumed to be indicative of resilience. Trained teams of divers collected data from sites between 5-10 m depth. Latent variables (e.g., fish condition, coral condition) are aggregate scores from individual metrics (e.g., fish length, coral colony size). Spatial interpolation Ecosystem condition for each survey station was designated as an attribute of each point. Using a reef layer for Micronesia, the barrier reef surrounding Yap was extracted and a 200 m buffer around the polygon was created. I conducted an IDW and kriging for survey sites across the 3 latent variables (fish, coral, and benthic habitat), as well as the aggregate ecosystem condition score. Using the clip function in ArcGIS, I extracted interpolated values for reef areas with no data. Results & Discussion General trends Spatial interpolation of coral reef indicators highlighted a gradient of reef health. Overall reef health showed a general decline from north to south, with a secondary gradient moving from east to west (Fig. 4). Similar patterns exist for fish condition (Fig. 5) and coral condition (Fig. 6). Benthic substrate condition exhibited a stronger east-west pattern. Methodological comparison Kriging and IDW tools in ArcGIS detected similar broad patterns. Generally, kriging approaches are more robust models that account for prediction error. Additionally, these models are less influenced by a single point., where IDW results (right panel in Fig. 4 - 7) can be prone to the bullseye effect. However, the patchiness of reef condition and presence of MPAs is best captured by IDW. Conservation/management prioritization Priority areas for conservation and management were identified using binary calculations for areas beyond 1 standard deviation of mean values. Three locations with high values for fisheries management were identified (Fig. 8). Two of the sites were located within existing MPAs, while the third is the most geographically isolated location on the island. The existing MPAs may provide adjacent areas with fisheries replenishment via spillover. Maintaining support for these areas should remain a top priority. The last location may serve as a defacto reserve, due to its isolation. Formal protection might be a consideration to prevent potential poaching. Three locations were also identified for potential coral restoration/rehabilitation efforts (Fig. 9). Two locations are on the northwest of the island, while the third is adjacent to the main shipping channel into the lagoon. Conclusion

Coral reef communities exhibit high levels of heterogeneity [14,15]. In addition, management tools for coral reefs can be spatially explicit (i.e., MPAs), recapitulating heterogeneity [16]. IDW spatial interpolation should be used as a preferred GIS tool as it best captures this effect. Identifying potential locations for conservation has been shown to maximize costs and utility of decisions [17]. Spatial tools can provide reef managers with both tools to support further conservation, as well as inform policy [18]. References 1. Wear, S. L. & Vega Thurber, R. Sewage pollution: Mitigation is key for coral reef stewardship. Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 1355, 15–30 (2015). 2. MacNeil, M. A. et al. Recovery potential of the world’s coral reef fishes. Nature 520, 341–344 (2015). 3. Spalding, M. D. & Brown, B. E. Warm-water coral reefs and climate change. Science (80-. ). 350, 769–771 (2015). 4. West, J. M. & Salm, R. V. Resistance and resilience to coral bleaching: implications for coral reef conservation and management. Conserv. Biol. 17, 956–967 (2003). 5. Norström, A. V. et al. Guiding coral reef futures in the Anthropocene. Front. Ecol. Environ. 14, 490–498 (2016). 6. McClanahan, T. R. et al. Prioritizing Key Resilience Indicators to Support Coral Reef Management in a Changing Climate. PLoS One 7, e42884 (2012). 7. Nash, K. L., Graham, N. A. J., Jennings, S., Wilson, S. K. & Bellwood, D. R. Herbivore cross-scale redundancy supports response diversity and promotes coral reef resilience. J. Appl. Ecol. 646–655 (2015). doi:10.1111/1365-2664.12430 8. Hughes, T. P., Bellwood, D. R., Folke, C. S., McCook, L. J. & Pandolfi, J. M. No-take areas, herbivory and coral reef resilience. Trends Ecol. Evol. 22, 1–3 (2007). 9. Venegas-Li, R., Cros, A., White, A. T. & Mora, C. Measuring conservation success with missing Marine Protected Area boundaries: A case study in the Coral Triangle. Ecol. Indic. 60, 119–124 (2016). 10. Heron, S. F. et al. Validation of Reef-Scale Thermal Stress Satellite Products for Coral Bleaching Monitoring. Remote Sens. 8, 59 (2016). 11. Rowlands, G. P. et al. Satellite imaging coral reef resilience at regional scale. A case-study from Saudi Arabia. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 64, 1222–1237 (2012). 12. Knudby, A., Jupiter, S. D., Roelfsema, C., Lyons, M. & Phinn, S. R. Mapping coral reef resilience indicators using field and remotely sensed data. Remote Sens. 5, 1311–1334 (2013). 13. Houk, P. et al. The Micronesia Challenge: Assessing the Relative Contribution of Stressors on Coral Reefs to Facilitate Science-to-Management Feedback. PLoS One 10, e0130823 (2015). 14. van Woesik, R. Processes Regulating Coral Communities. Comments Theor. Biol. 7, 201–214 (2002). 15. Dornelas, M., Connolly, S. R. & Hughes, T. P. Coral reef diversity refutes the neutral theory of biodiversity. Nature 440, 80–82 (2006). 16. Russ, G. R. & Alcala, A. C. Do marine reserves export adult fish biomass? Evidence from Apo Island, central Philippines. Mar. Ecol. Prog. Ser. 132, 1–9 (1996). 17. Scholz, A. J., Steinback, C., Kruse, S. A., Mertens, M. & Silverman, H. Incorporation of Spatial and Economic Analyses of Human-Use Data in the Design of Marine Protected Areas. Conserv. Biol. 25, 485–492 (2011). 18. Wedding, L. M. et al. Advancing the integration of spatial data to map human and natural drivers on coral reefs. PLoS One 13, e0189792 (2018). ...now that's a good coding joke for you!

Hi everyone! Welcome to my personal website. I'm a first-year PhD student in geography at Oregon State University. I'll be using this space as a place to share my thoughts and communicate my science. Hopefully you find my musings thought provoking and I hope to engage with you all. Mahalo, Steven |

Steven M. Johnson

Aloha and Hafa Adai! I'm an Assistant Professor at Cornell University. As a researcher and knowledge enthusiast, I enjoy learning about social-ecological systems, the ocean, and the people who rely on it. Archives

April 2022

Categories |

Location

|

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed